Missy Dunaway on Narrative Pictures

Welcome back to the ‘In a Nutshell’ section. This is part of an ongoing project in collaboration with King’s College, London to engage with artists (by interviewing them) and to present the content with a brief introductory summary that contextualizes the artist’s work within current philosophical debates.

Our 10th interview features Missy Dunaway. Missy is an artist and illustrator whose career was launched with an inaugural post of her visual diary on flickr attracting over 750,000 likes. The response speaks to the immediacy and expressiveness of her work. She is an artist and illustrator who tells stories with pictures.

Missy received her Bachelor’s Degree in Humanities and Arts from Carnegie Mellon University in 2010. She was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship in 2013 to research Anatolian textiles in Turkey. Her paintings have been featured by Penguin Random House India, Travel + Leisure, and The National Audubon Society and are displayed at institutions including Carnegie Mellon University and the Folger Shakespeare Library of Washington DC. In 2019, she was named the inaugural Four Seasons Envoy, which she traveled to Four Seasons Resort The Nam Hai in Hoi An, Vietnam. Later that year, she was awarded a New Student Scholarship to the Academy of Realist Art in Boston, where she is currently studying.

Follow Missy Dunaway on her website. Learn more about the King’s Cultural Institute and the CPA.

THE PHILOSOPHY OF NARRATIVES

We seem to have an insatiable appetite for stories. Not just stories about far-away lands and daring-do from long ago heroes, but narratives that are woven from the incessant and teeming activity in the world around us. Recently, theorists have suggested that this ubiquitous desire to tell and listen to stories is primitively bound up with the notion of ‘a self’ or ‘oneself’. But what does that mean?

In philosophy, when we want to analyse stories, we tend to do so under the umbrella term ‘narrative’. However, one might worry that the word popularity of discussions about narrative across the broad spheres of perception, mind and aesthetics has led to an overuse problem. The result of which is that it is now unclear to us what exactly narrative is, or what it can be formed out of. Words? Music? Pictures?

Theorists agree on the following points. Narratives typically have three features. They have coherence, revealing some connection between the narrated events. They have meaningfulness, revealing how the narrator, or the characters within the narrative, understood those events. And they have evaluative and emotional import, revealing how the narrative’s characters or its narrator feel about those events.

From this, things seems clear enough. Narrative is more than a chronicle of events laid out in a timeline. My shopping list isn’t a narrative and nor is my diary. Narrative involves something with more psychological punch. It requires a point of view on events as well conveying that events are going on somewhere (not necessarily round here or round about now). This has led some to think that narratives, whether found in pictures or books, are constituted by characters who tell us the story. Yet, this can seem weird when we think of narrative pictures that do not feature any sort of figure or character.

Given this, one might be suspicious that pictures can be narrative. Those who say they can’t point out that pictures are snapshots of time, rather than passages of it. They are just not the right kind of thing to contain a story (which links together events over time). Yet, Bence Nanay has replied to this by arguing that doubters confuse how a picture may depict an instant with a picture’s capacity or potential to represent a passage of time. That means pictures can sustain degrees of narrativity after all.

The kind of philosophical debate can seem bizarre to artists however. Artists are much clearer about the role narrative plays in pictorial experiences. And today I spoke to Missy Dunaway to find out more about how makers of pictures see narrative functioning in the work.

Transcript excerpts from Interview

VB: Hi Missy – it’s lovely to speak to you. Where are you right now?

MD: I'm in the Portland Gallery, which is in Maine, USA. (Missy works at the Gallery as well as being one of their featured artists in the current exhibition).

VB: Congratulations on the exhibition. It’s been exciting following the progress of these larger works and I’m looking forward to our discussion about narrative pictures.

MD: Me, too! Whenever I think of narrative artwork I recall a quote from the book ‘Hawthorne on Painting’ by Charles Hawthorne, that the amateur art observer will determine the value of an image by its narrative quality—think of a sprawling neoclassical painting that relays an entire battle scene. Whereas an artist will determine the value of an image by its emotional impact or atmosphere—such as an impressionist image. Hawthorne himself was an impressionist painter. Even so, this opinion strikes me as odd since it seems to me it shouldn’t matter how someone retrieves value from a picture – just as long as they do.

Pictorial stories have been an essential tool for conveying culture, history, political ideas and other information for illiterate people who couldn’t access written history. The visual arts can be very inclusive, maybe because image is a universal language of sorts.

VB: I sense this suggested ‘hierarchy’ of artistic content rankles with you?

MD: Yes. Whether a picture conveys a story, an emotion, or it simply renders an object, it has value.

VB: How does this link to the paintings in the exhibition currently – your large scale versions of original paintings in your moleskine travel diary?

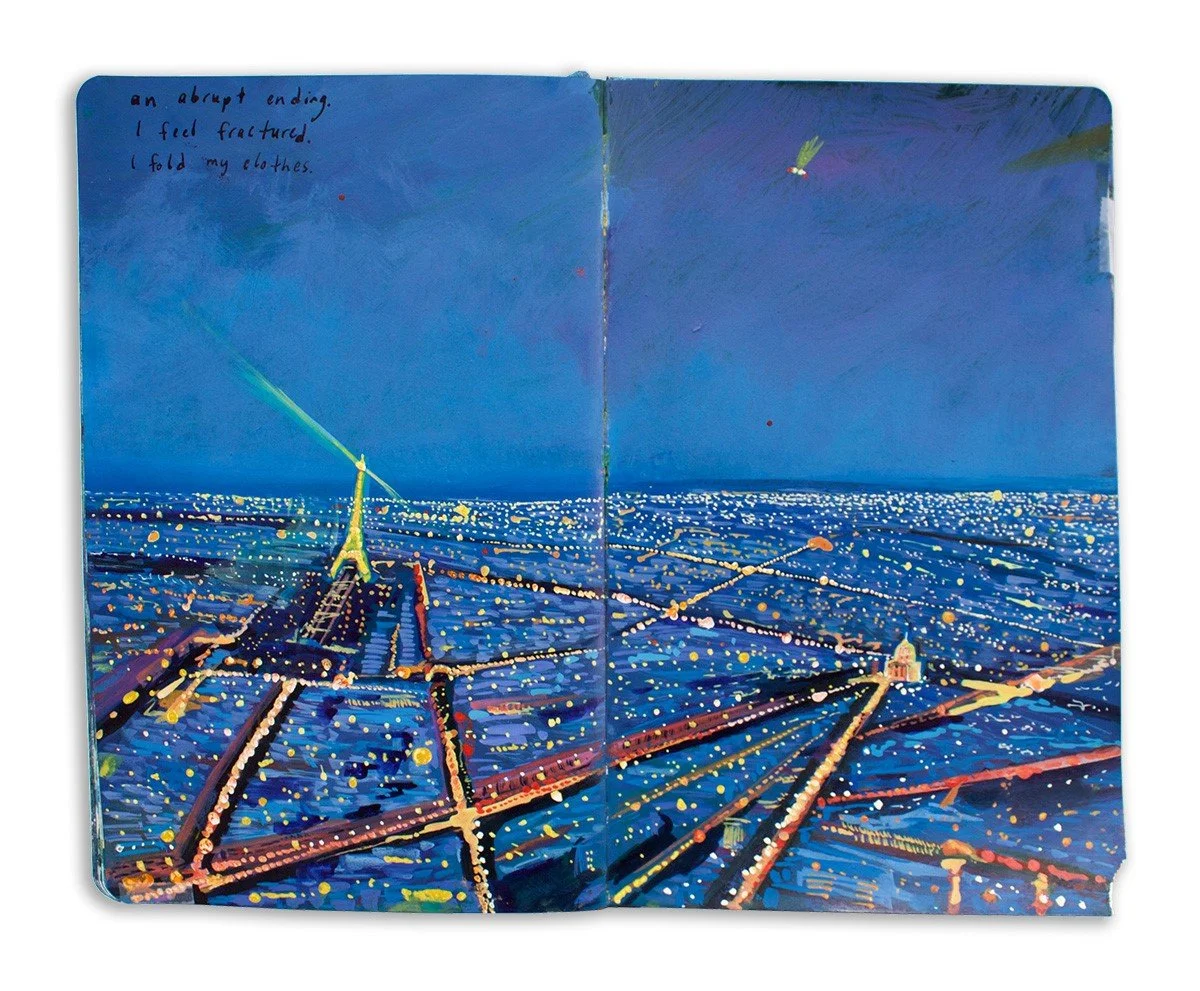

The Stars Above and the Stars Below - Large Acrylic Ink on Paper (inspired by Travel Journal page) © Missy Dunaway

MD: Yes, these paintings are larger versions of favourite pages from my visual diary, a book of paintings. A diary does have a storytelling element in a way, but it’s less about recording a sequence of events than it is about reflecting on those events. I paint the scene usually after some time has passed – sometimes when I am in a completely different location. I want to capture how each moment made me feel; how I understand it through the lens of time.

My paintings depict memories, rather than moments. It’s a subtle difference, but I suppose it means the scene seeks to capture emotion rather than facts. I want the viewer to feel the same way when they look at the picture as I do when I look back on the scene.

Original Travel Journal painting - Acrylic Ink on Paper © Missy Dunaway

VB: So are these paintings meditations on moments in your life?

MD: That’s correct. The mind manipulates memories so dramatically and continues to change them over the years. I’m often afraid I’ll forget a special moment, or change it, or lose details that are important to me. And so I paint to preserve an event. I quite like waiting until time passes so the memory becomes coloured by nostalgia. It’s a satisfying process because I get to time travel in my imagination and return to my favourite places on the page.

Although I disagree with that quote by Hawthorne, I admittedly take the same approach in my artwork. I prefer that my paintings communicate an emotion rather than a narrative because emotions are relatable to a wider audience. I hope that my paintings remind people of their own travel memories, or imagine where they might go in the future. Even if they have never been to Morocco before, I hope that my paintings of Morocco recall that general spirit of travel they have experienced. My personal narrative is specific to me, but emotions are experienced by all.

VB: That brings me to the first painting I want to ask you to talk about, The Stars Above and the Stars Below

MD: That painting is about leaving Paris after a break-up. Even though it’s sad, it’s still a beautiful scene no matter how it was coloured by events. The original version in the book has a handwritten poem on it that reads, ‘An abrupt ending. I feel fractured. I fold my clothes’. I decided to exclude that poem from the large version because without it, the tone is ambiguous. Are you leaving or arriving, is this a melancholy scene or an exciting one? Gallery visitors tend to think it is a moment of arrival. The words would have pinned a negative feeling and might exclude some people from experiencing it as they want. I’ve noticed that most people use art as a way to imagine themselves into the picture. Which is fine with me. I wouldn’t put my artwork into the world otherwise.

From Far Away (pages from the Travel Journal) © Missy Dunaway

VB: Can I ask about The Dog on the Beach and this sense we gain when looking at your pictures over a sequence of ‘the world as seen through Missy’s eyes’. What do you think of that?

MD: That’s exactly true because most paintings begin as snapshots taken with my camera from my point-of-view. Taking photos is my way of taking notes. The photos aren’t interesting exactly, they are just reminders of what to paint later. I have hundreds of such unimpressive snaps. Originally, I hesitated painting that scene because golden retrievers are such sentimental beings! However, her expression was so sweet and genuine and charming, I had to paint her. That was my husband’s family dog who has since passed away, so the picture is even more special now to our family.

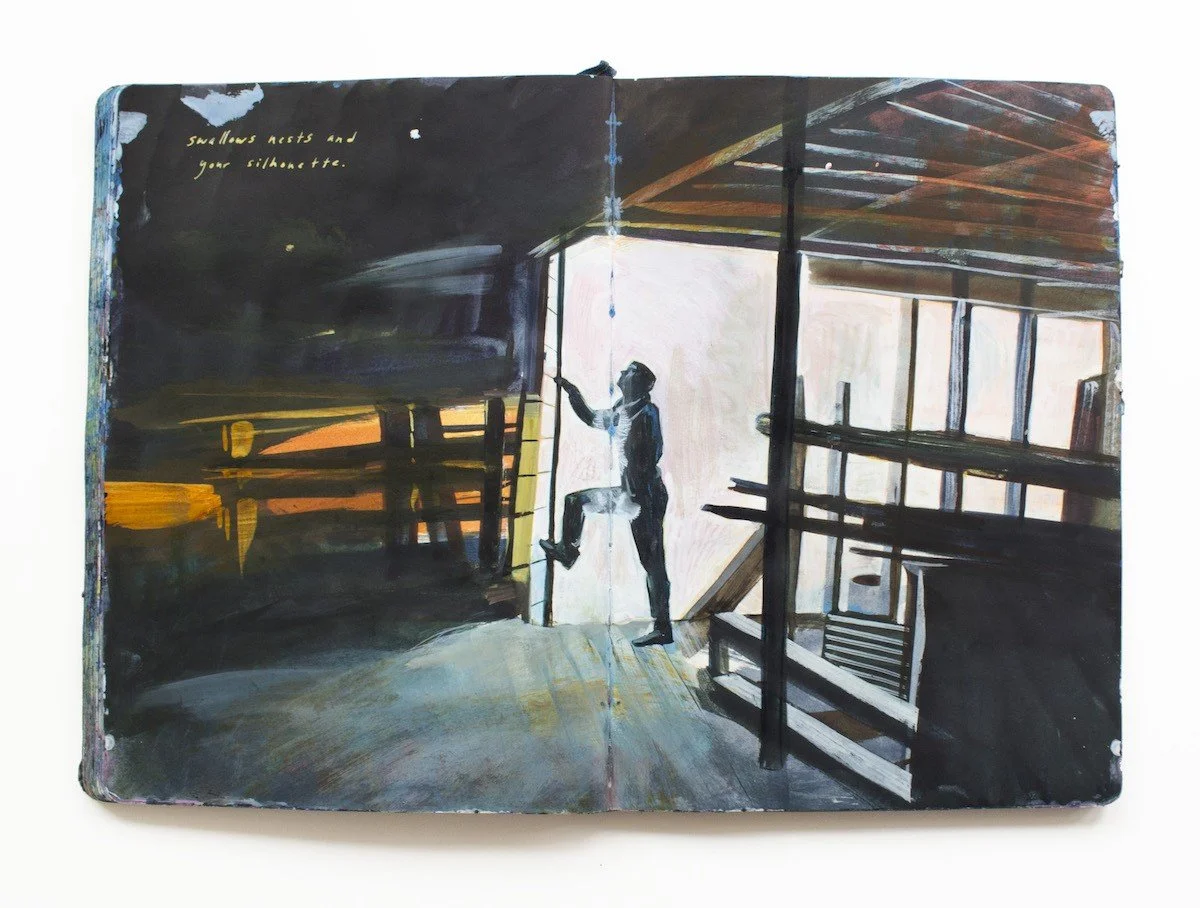

Joe in the Barn - Acrylic Ink on Paper (Travel Journal) © Missy Dunaway

VB: And Finally, could you tell us more about the picture of Joe in the Barn – looking for swallows?

MD: That scene shows Joe gazing up at some swallow’s nests inside an abandoned barn in southern Maine. I was standing in the back of the barn in shadow. His figure looked so striking in silhouette from where I was standing, so I took a photo and painted it about a month later when I had the time. That painting is quite different for me because it’s almost a black and white image, and as you know, I usually cram as many colors as I can into a scene! I used a stark palette to help the scene feel cold, as it was the beginning of winter.

Further Reading

Gombrich, E. H. 1964. Moment and Movement in Art. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 27, pp. 293-306

Le Poidevin, R. & MacBeath, M. 1993. The Philosophy of time, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Matravers, D. A. 2014. Fiction and narrative, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nanay, B. 2009. Narrative Pictures. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 67, 119-129.

Simicek, K. 2015. Beyond Narrative: Poetry, Emotion and the Perspectival View. British Journal of Aesthetics, 55, 497-513.

Velleman, J. D. 2003. Narrative explanation. Philosophical Review, 112, 1-25.